Planning a Bike Tour

Salivating on Google Maps. Deception Pass. Fidalgo Island, Washington.

Why?

When I tell people that I actually enjoy going on long, multi-day bicycle rides, I encounter a diverse range of responses.

Those who “get it” will share feelings of mutual excitement, respect and a special sympathy. These folks are typically hikers, runners, fellow cyclists, or other flavors of wandering souls who understand the appeal and psychic effects of self-powered adventuring through urban and natural geographies.

Others will stare at me with a mix of admiration and disbelief. You’re biking how far? they say, shaking their head. To the uninitiated, an orientation like mine implies either a near superhuman endurance or a sadistic sense of pleasure. It might also suggest that you are struggling to recover from some personal affliction or tragedy. You’ll be just like Reese Witherspoon in Wild!

Still others will simply ask why? As in, why wouldn’t you just drive there?

Well, there are several reasons.

Quiet mind times

When you spend good, long hours exploring the beauty of your surrounding environment, looking at seemingly endless terrain, conversing with companions of the road, or reflecting on the universe and your purpose in it, you become attuned to your inner self. These periods of introspection, which I like to call quiet mind times, are needed by all people but seemingly enjoyed by only few.

It is easy to tune out. Life often requires us to focus on getting through places for practical reasons (getting to school, getting to work, etc), such that we overlook the experience of being in them. In a Field Guide to Getting Lost, Rebecca Solnit celebrates the value of the small wonders that many of us tend to ignore or hustle past without noticing at all. Part of the philosophy is no philosophy at all - rather a sense of wonder, an open mind, and the capacity to see and feel more than just what can be defined.

When I walk, what happens is more vague, more ambiguous — and in many circumstances much richer. I am out in the world. It’s exercise, though not so quantifiably as on a treadmill in a gym with a digital readout. It’s myriad little epiphanies and encounters that knit me more tightly into my place and maybe enhance the place overall. The carbon emissions are essentially nil. Many more benefits are more subjective, more ethereal — and more wordy. You can’t describe them in a few familiar phrases; and if you’re not practiced at describing them, you may not be able to articulate them at all. It is difficult to value what cannot be named. Since someone makes money every time you buy a car or fill it up, there’s a whole commercial language built around getting us to drive; there’s little or no language promoting the free act of walking. - Rebecca Solnit

The bicycle as a psychogeographic tool

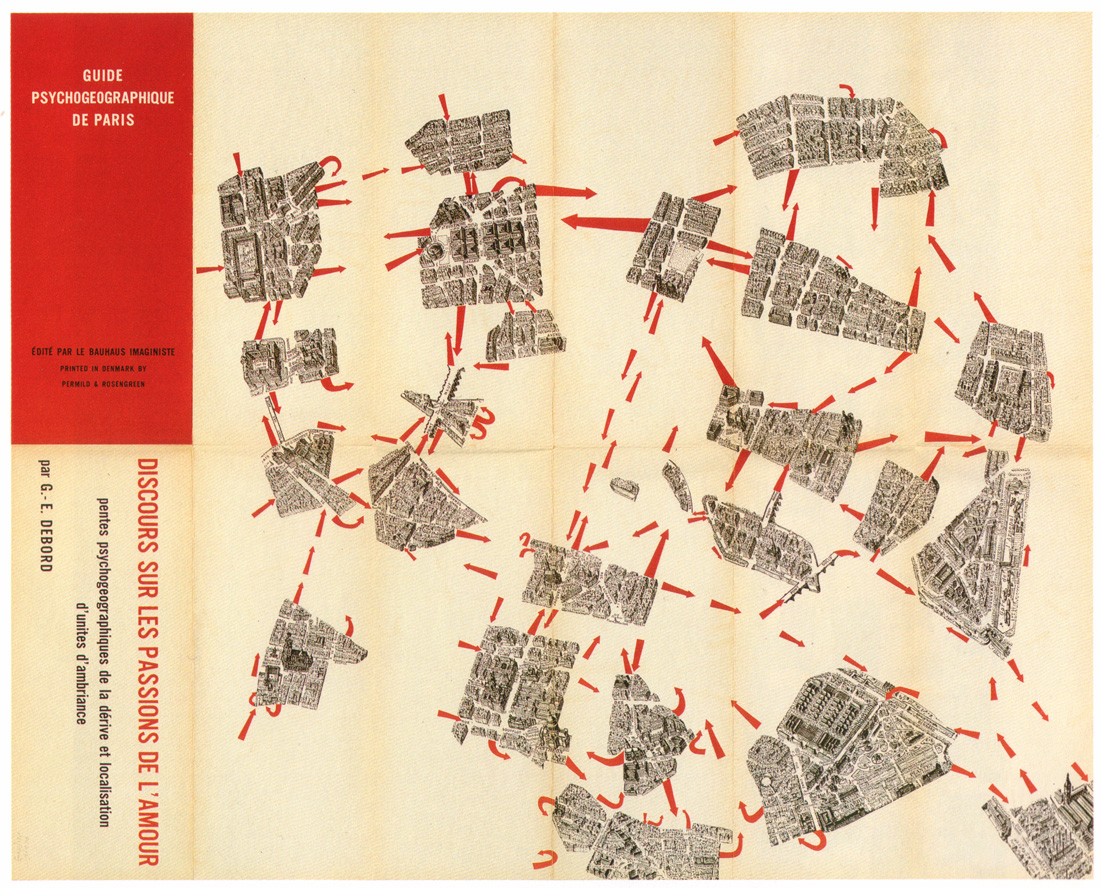

The physical environment impacts our internal environment, and vice versa. Psychogeography is an approach to understanding the conscious and subconscious effects of the geographic environment on human emotions and behavior. It originated as a sort of tongue-in-cheek, art-imitating-science branch of social geography that posits playful “drifting” around urban environments as a tool for sparking a new awareness of the built environment. Psychogeography was originally developed in the 1950s by an avant-garde group of Parisian artists and theorists known as The Letterist International, who might be thought of as French counterparts of the American Beat Generation. An interest in this field - if one can call it that - continues to persist. There is even a conference in New York City dedicated to psychogeography called Psy.Geo.Conflux.

Most of us follow a small set of preprogrammed instructions as we wander through the city: office, day care, grocery store, home. If you track your own path through a typical day, you’ll soon discover that your journey is habitual, that you’re slowly wearing a canyon through the same streets, the same sidewalks, day after day. Psychogeography encourages us to buck the rut, to follow some new logic that lets us experience our landscape anew, that forces us to truly see what we’d otherwise ignore. Chance and randomness are what’s exciting. - Joseph Hart, A New Way of Walking

Psychogeography encapsulates a toolbox of playful strategies for exploring urban and natural environments. Principle among them is the Dérive (French for “drift”), which is defined here as an aimless, random drifting through a place, guided by whim and an awareness of how different spaces draw you in or repel you. Artist and cartographer Denis Wood defines it as:

Dérive: “A mode of experimental behavior linked to the condition of urban society: a technique of transient passage through varied ambiances.” Situationists used “ambiance” to refer to the feeling or mood associated with a place, to its character, tone, or to the effect or appeal it might have; but they also used it to refer to the place itself, especially to the small, neighborhood-sized chunks of the city they called unités d’ambiance or unities of ambiance, parts of the city with an especially powerful urban atmosphere. Denis Wood, Lynch Debord: About Two Psychogeographies

For example, the below map contains fragments of street maps (“unities of ambiance”, hah) cut to indicate each area’s defenses and exits. The red arrows symbolize the psychogeographic slopes exerted on the city-surfing wanderers, pulling them from one urban universe to the next.

Guy Debord, Guide Psychogéographique de Paris

Guy Debord, Guide Psychogéographique de Paris

Contemporary mapping projects such as Emotional Cartography by Christian Nold use bio-mapping as a tool for self-awareness. By actively monitoring one’s arousal while traversing through physical space, one creates a medium for reflection in which feelings that might otherwise fall beneath the radar of everyday awareness are captured.

Most psychogeographic reports of dérive involve wandering a city by foot to achieve a heightened sense of emotional and spatial awareness. I believe that the bicycle, too, is a tool well-suited for the job. The bicycle enables us to experience and catalogue a diverse variety of environments. This allows for the detection of fluctuating emotionscapes not only from one urban block to the next, but in the transition between vastly different landscapes, from urban to rural, mountains to plains, desert to coastline. It is perhaps a practice nuanced enough to warrant its own term… Cycle-geography, if you will :)

In summary: Why, you ask? Because riding a bike is fun!

How?

Now that you have the Why - let’s move on to the How.

How does one plan and ride a long bicycle tour?

Like most problems, it helps to break things up into parts. For example, I am planning to bike the pacific coast this summer, which has been a dream of mine for quite some time. When prospecting a bicycle tour, I generally start by doing some research to see if anyone else has ridden and documented a similar route. As it turns out in this case - tons of people have.

Some of my favorite sources range from the institutional Adventure Cycling Association to the homegrown Crazy Guy on a Bike forum, which is an amazing repository of tips and stories from other wide-eyed guys and girls who have gone around the bend. The best resource, of course, is local knowledge from friends and “real live people” who live or have spent time along your route.

What happens next is a fervent mix of theft and creation. I steal what I like - trails, campgrounds, hot springs, hostels, burger joints, dive bars, beaches, bridges, ferries, cities, towns, short cuts, long cuts - and combine them with some new ideas of my own to create a unique hodgepodge of psychogeographic delight.

Planning the route

I use Google’s My Maps to plan the route and save points of interest like campgrounds and cheap lodging options, and regular old Google Maps (yes, they are separate but related products) to easily compare and preview alternate routes. The Street View functionality is particularly helpful because it can give you a sense for whether or not a particular section of the route is something that you want to bike. For example, the Coos Bay Bridge in North Bend, Oregon was not designed with human-powered travelers in mind and may be too intense for some bikers. But not to worry, there is a well-documented route for those who would prefer to avoid this bridge.

Coos Bay Bridge. North Bend, Oregon. Looks pretty intense… maybe I’ll take the bypass route.

Coos Bay Bridge. North Bend, Oregon. Looks pretty intense… maybe I’ll take the bypass route.

Planning a trip like this is a fun, iterative process involving tradeoffs around every corner. For example, should I ride from Vancouver to Seattle through Bellingham? Or should I explore Vancouver Island and the San Juans, skipping Seattle altogether? Or both? As you’ll see below, I chose both and am looking forward to island-hopping from Vancouver to Seattle (no one said ferries are illegal!).

Bluffs Trail, Andrew Molera State Park. Big Sur, California.

Bluffs Trail, Andrew Molera State Park. Big Sur, California.

Below is my route as it currently stands. It will likely grow to include more attractions and special places over the coming weeks. You can toggle on and off the campgrounds and other attractions that I have identified along the route (open the sidebar and scroll down to do so).

Go out and ride

As for actually riding this thing… follow along below!